SUBSCRIBE!

for updates to my blog

and to my events schedule

My Dawson journey began at the end of the road – literally

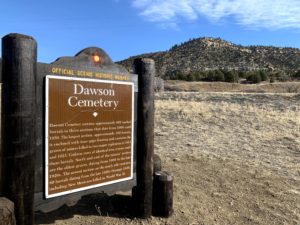

A historical marker welcomes visitors to Dawson Cemetery.

The unpaved roadway leading from State Road 505 to Dawson Cemetery, to be kind, is pretty remote. No businesses. No homes. No people.

Not that I was surprised. I had read enough stories, seen enough photographs, and watched enough videos to prepare myself for my first visit to the historic cemetery,

Or so I thought.

The date was Jan. 17, 2019. I left at 7 a.m. for what would be a 227-mile, 3½-hour trip from my Albuquerque home. The plan was to drive to the cemetery, spend 45 minutes there, then head north for a prearranged noon tour and interview with Raton Museum curator Roger Sanchez to learn more about Dawson’s history.

I couldn’t have asked for a better New Mexico winter’s day. By the time I turned onto the road leading to the cemetery, the sun had peeked through picturesque cirrus-type clouds, and the temperature was well on its way into the 50s.

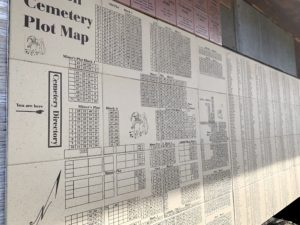

A large plot map near the entrance to the cemetery helps visitors find the graves of their loved ones.

As it turns out, I needn’t have worried about inadvertently driving past the cemetery. The bumpy, 5-mile road ends abruptly at the foot of a locked pasture gate displaying a sign with bold, black lettering: “NO TRESPASSING. HUNTING BY WRITTEN PERMISSION ONLY. Colfax Land & Cattle Company.”

Clearly, I had come to the end of the road, so to speak.

Glancing back to my right, I could make out in the distance some of the white iron crosses that mark the gravesites for many of the 383 miners who lost their lives in two major mine explosions in 1913 and 1923 – the 263 killed in the first earning the grim distinction as the second-worst in American history. I backed up, turned toward the cemetery, and parked a short walk from the metal gate. As I stepped out of my car, I realized I was alone, the only sound the faint chirping of unseen birds in the distance.

That’s when I first felt my heart pounding in my chest.

Boom-boom. Boom-boom. Boom-boom.

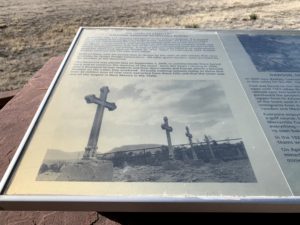

Poster boards provide visitors with a brief history of the old coal town.

Inside the cemetery gate, there was much to see before heading toward the graves: A massive plot map that directs visitors to the burial sites of their loved ones. Plastic-encased poster boards that chronicle the history of Dawson. A smattering of plaques memorializing key events in the town’s history. A mailbox containing pen and paper so visitors can sign their names or leave notes to the volunteer caretakers.

Boom-boom. Boom-boom. Boom-boom.

I entered the burial grounds, walking slowly among the hundreds of white iron crosses, my eyes fixated on the names etched onto each as I passed. Gavino Calderon. Fermin Gallegos. Isadoro Gomez. George Makris. Francisco Mandato. Daniel Romero. Dom Santi.

Boom-boom. Boom-boom. Boom-boom.

The names didn’t mean much to me that day. Since that time, however, I’ve become more familiar with some of their stories. Santi was among an unfathomable 10 members of an Italian family to die in the 1913 explosion. Makris was joined in death that day by his brother, Costa, and George’s grandson and wife visited George’s grave in 2007. Romero’s body was among the first 28 to be identified.

Boom-boom. Boom-boom. Boom-boom.

Worried I would be late for my noon appointment, I reluctantly exited the cemetery, walked back to my car, and drove off toward my next stop in Raton.

To this day, I don’t know what prompted my heart to beat like a drum that January morning. Nor do I recall how long it took to resume its regular rhythm after driving away.

No matter. I now knew for certain what I had suspected all along: The writing of Crosses of Iron would be no academic exercise.

Boom- boom.

Crosses of Iron

by Nick Pappas

Now available to order from:

University of New Mexico Press

… and other booksellers.

Audiobook version available to order from …

… and other audiobook sellers.