SUBSCRIBE!

for updates to my blog

and to my events schedule

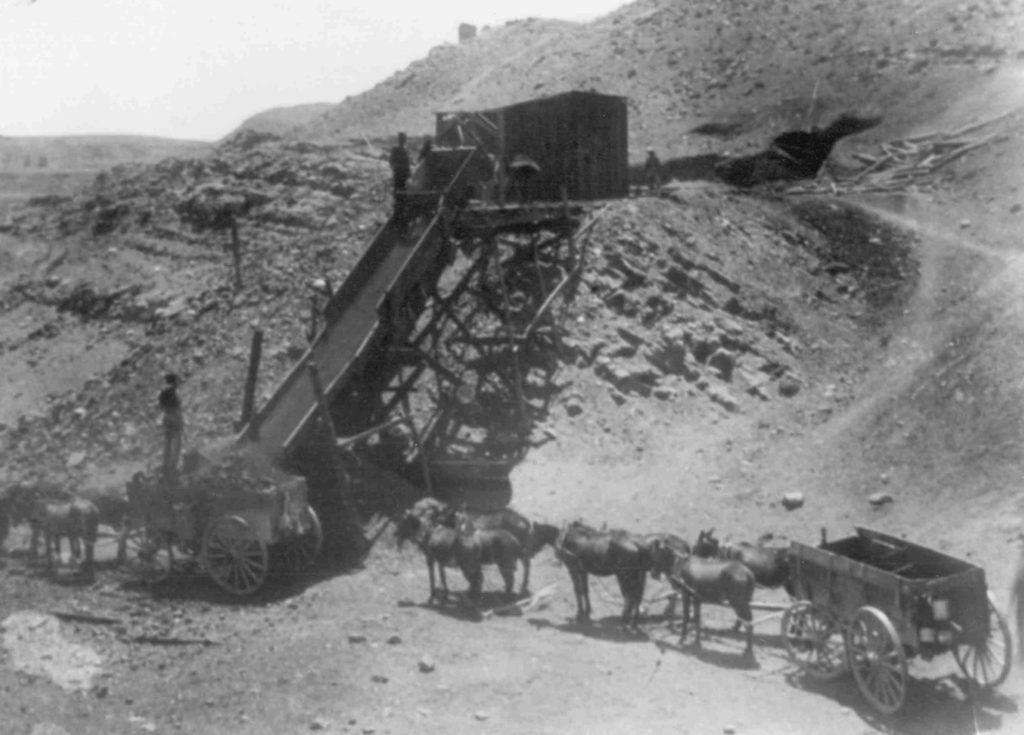

Carthage rescue mission went south fast for two Dawson miners

The news item couldn’t have been more innocuous.

Thomas Brown and David Murphy of Dawson, N.M., who were in Albuquerque Monday, left for home by automobile yesterday.

That snippet appeared in the Albuquerque Morning Journal on Feb. 27, 1918, sandwiched between word that Texas cattleman U. Keen was in town for a few days and Mrs. Earl Bowdich was bound for Kansas to visit her husband at Camp Funston.

Despite the press report, it’s unlikely Brown and Murphy ever made it back to Dawson. On that Tuesday, the trained rescue men were en route to a coal mine fire more than 300 miles away at the Government Mine at Carthage in south-central New Mexico.

By 3:30 p.m., they were at the mine.

By 6:21 p.m., they were inside the mine.

By 7:54 p.m., they were clinging to their lives.

Recruited for mission

Four days earlier, New Mexico Mine Inspector W.W. Risdon was notified by the president of the Carthage Fuel Co. that the mine had caught fire on Thursday, Feb. 21. Risdon, who was in Dawson at the time, immediately set out for Carthage, according to his account published in the 1918 annual report.

Upon his arrival Saturday, Risdon learned everyone had escaped without injury and that the mine had been sealed. Risdon suggested to mine President Powell Stackhouse Jr. that he summon a U.S. Bureau of Mines rescue car and ask Dawson General Manager T.H. O’Brien to send two experienced rescue men.

Brown was superintendent of Dawson mine No. 2; Murphy a Dawson mine inspector. They reached Carthage by train Tuesday at 3:30 p.m., joining Risdon and the rescue team from the Bureau of Mines.

At 4:15 p.m., four men from the bureau’s crew prepared to enter the mine. Each was equipped with a Fleuss breathing apparatus — a rudimentary oxygen rebreather device — and they carried with them a safety lamp, a caged sparrow, and a caged mouse.

The crude gas-detection system worked like a charm. The lamp was out in seconds. The sparrow was dead within 25 feet. The mouse was destined for a similar fate before the crew pulled an about-face and exited the mine.

James Cunningham, the bureau’s team leader, was reluctant to try again with his less experienced men and called for Brown and Murphy. Both were trained in rescue work and had experience combatting mine fires.

This second crew – Cunningham, Brown, Murphy, and two others – entered the mine at 6:21 p.m. with the goal of covering roughly 700 feet, where there was a door that opened outside into fresh air. The men made their mark without incident; the same couldn’t be said for their mouse.

After walking a bit further toward the source of the fire, the crew began its return to the mine entrance. The men had retraced about a third of their steps when someone noticed Murphy was struggling to breathe.

Cunningham promptly adjusted Murphy’s breathing apparatus, which brought immediate relief. Murphy assured his crewmates he was fine and would need no further assistance.

Before long, however, Murphy again showed signs of distress. To make matters worse, while Cunningham was tending to Murphy, he noticed Brown looked wobbly, too. Within minutes, both men were down.

Unable to carry them out, the rescue team exited the mine, refreshed their oxygen tanks, and returned in a mine car to retrieve the two men. They found Brown exactly as they had left him, but Murphy had turned onto his back and disconnected his breathing apparatus, his mouth open to the poisonous gases.

Brown recovered. Murphy did not.

“Work to resuscitate Murphy began 7:54 and continued until about 12:01,” Risdon wrote in his report. “Two doctors were in attendance and at no time were either of them positive that they could detect any sign of life.”

So what happened?

One theory advanced years later in a Bureau of Mines information circular was that Murphy was unfamiliar with the older Fleuss breathing apparatus used in Carthage, having been trained on the more advanced Draeger apparatus.

But the circular published in April 1944 – 26 years after the incident – took it one step further. Author G.W. Grove, supervising engineer for the bureau’s District A. Health and Safety Service, suggested Brown and Murphy bore some responsibility for the tragic incident.

“It is reported that the team captain had some difficulty in controlling Murphy and his companion while they were on the exploration trip, and that they talked to each other incessantly before the accident,” Grove wrote in the circular titled Loss of Life Among Wearers of Oxygen Breathing Apparatus. “It is surmised that each of them inhaled carbon monoxide around their mouthpieces while talking.”

Epilogue

Risdon wrote in his 1918 report that he had “great respect for Murphy’s knowledge and experience in mines,” perhaps greater than in “any of the other men in the party.” And, contrary to those later reports, Murphy had assured him he had full confidence in the Fleuss breathing apparatus.

Still, Risdon advised him to be careful before entering the mine, emphasizing there were no lives at stake.

“He said to me, ‘I am not going to take any chances,’” Risdon said, “’and you don’t need to be uneasy about me.’”

Murphy, the son of an Irish miner, was 44 years old. His body, escorted by his colleague Brown, was taken to Trinidad, Colorado, where he was buried in the Masonic Cemetery.

Murphy is one of three rescue men associated with Dawson to die in this manner. James Laird and William Poyser were killed under similar circumstances during a rescue mission inside Dawson mine No. 2 after the Oct. 22, 1913, explosion that killed 261 other miners.

Laird and Murphy share the same resting grounds in Trinidad; Poyser is buried at Fairmont Cemetery in Raton.

Crosses of Iron

by Nick Pappas

Now available to order from:

University of New Mexico Press

… and other booksellers.

Audiobook version available to order from …

… and other audiobook sellers.