SUBSCRIBE!

for updates to my blog

and to my events schedule

The story behind Dawson Railway’s deadly derailment of 1922

Poor Frank Hinds never saw it coming.

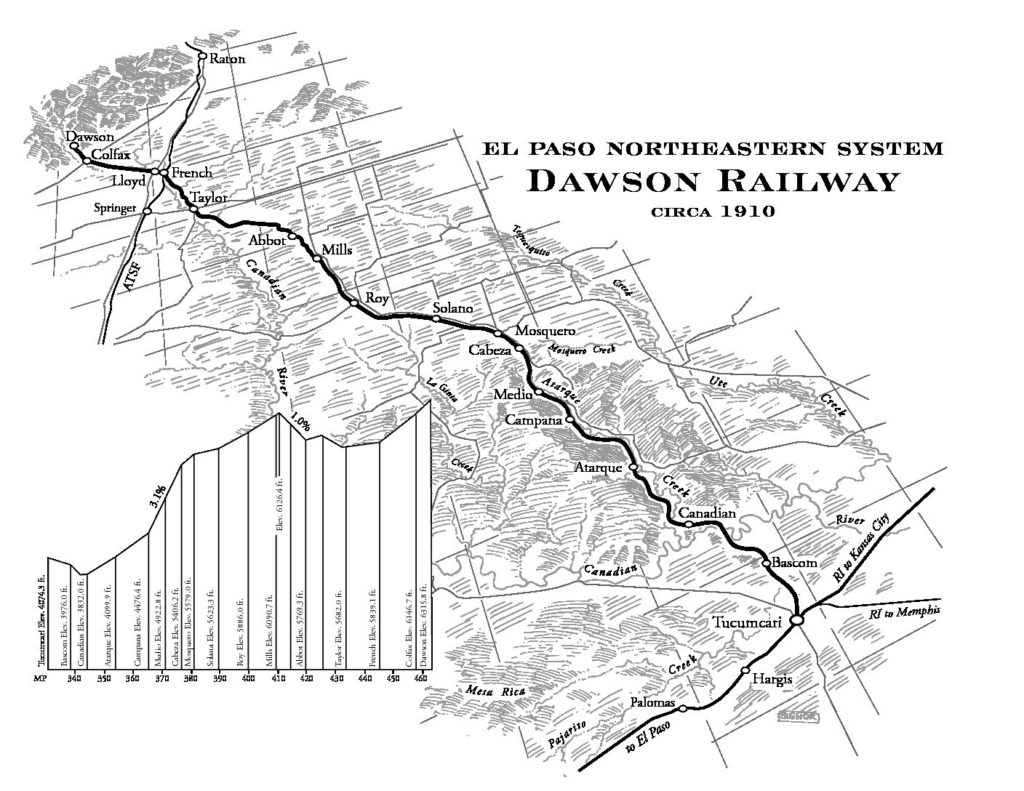

A longtime engineer for the El Paso & Southwestern Railroad, Hinds had no reason to suspect anything but a routine run when he pulled out of Dawson with carloads of coal ticketed for his hometown of Tucumcari.

After all, trains had been making this 132-mile trip over the grassy plains of northeastern New Mexico without major incident for nearly 20 years – if you discount the great train depot heist of 1908 – ever since the Dawson Railway made its debut on Jan. 17, 1903.

Sadly, there was nothing routine about it.

Engine trouble

On Oct. 25, 1922, Hinds and his crew left Dawson with 43 cars of coal and a caboose, expecting to arrive at the end of the line in Tucumcari around suppertime. Here the coal would be handed off to other rail lines for delivery to in-state and out-of-state markets.

But Hinds experienced trouble with Engine 299, prompting him to pull up at Solana station – roughly halfway to Tucumcari – to seek help. Engine 286, based in Tucumcari, arrived at 5:45 p.m. with instructions to haul the balky engine and its precious cargo back to Tucumcari.

After the two engines were coupled, Engine 286 began the 13-mile trip to Cabeza. All westbound trains had to stop here for an inspection of their air brakes before approaching a five-mile stretch of track with a 2 percent descending grade.

That inspection never came.

The train rushed past Cabeza and continued to pick up speed until it jumped the track 2½ miles later at 65 miles an hour at 6:50 p.m. All but seven of the coal cars derailed.

Early newspaper reports painted a grim picture.

“So great was the momentum that eight coal cars went by the second engine, No. 299, which had crashed into the solid rock of the cut,” The Tucumcari News reported. “Engine 286 is lying on its right side. Both locomotives seemed to be total wrecks … The derailed coal cars were smashed to pieces.”

The damage would have been worse were it not for some fast thinking by three workers riding in the caboose. Once they realized the train was out of control, they uncoupled the car and applied the hand brakes, bringing it to a stop “just before they reached the derailment,” according to the newspaper.

So what happened?

In a report to the Interstate Commerce Commission dated Dec. 11, 1922, Bureau of Safety Chief W.P. Borland placed the blame squarely on the shoulders of Engine 286 engineer M.B. Carroll and his crew for not conducting a brake test before leaving Solana.

Specifically, Borland cited Carroll’s violation of Rule 31, which calls for an engineer to test the brakes after “coupling to train, and before leaving a terminal or car inspection station.”

“This accident was caused by failure of the crew … to make an air-brake test after the relief engine was coupled on,” he wrote.

“Had proper tests been made before departure from Solana, it would undoubtedly have been discovered that the brake pipe was not properly connected and that the air brakes were not operating throughout the train, and necessary corrective measures could then have been taken.”

Two people were killed in the crash.

Hinds died en route to a hospital in El Paso, Texas, of a “crushing injury pelvis,” according to his death certificate. The 49-year-old Detroit native had worked for the EP&SW for 25 years. The body of Hinds’ brakeman, J.B. Cantrell, 27, wasn’t found until three days later.

Carroll, engineer of the relief engine, was pulled from the wreckage by rescue teams after five hours and taken to a hospital in Tucumcari, where he recovered from his injuries. Joe Morgan, his fireman, was found unconscious after jumping from the train, but he too recovered.

As it turns out, the fatal train derailment wasn’t the only such accident to be linked to Tucumcari.

On Aug. 29, 1933, in a driving rainstorm, a Golden State Limited transcontinental train plunged through a washed-out bridge four miles west of the city, killing 11 and injuring 46.

Among the dead: Paul Cook, a Southern Pacific bridge inspector, who was on his way to inspect the bridge once he reached Tucumcari.

“He was going to Tucumcari to inspect possible damage by recent heavy rains,” Bessie Cook, his widow, told the El Paso Herald-Post. “He never got there –“

Crosses of Iron

by Nick Pappas

Now available to order from:

University of New Mexico Press

… and other booksellers.

Audiobook version available to order from …

… and other audiobook sellers.