SUBSCRIBE!

for updates to my blog

and to my events schedule

What’s an opera house doing in the middle of a New Mexico coal town?

For a New Mexico coal town forever linked to two of the deadliest mine disasters in the nation’s history, Sept. 28, 1907, is remembered as a much happier occasion.

On that night, 1,000 people –– 20 to 25 percent of the town’s population – came out to patronize a new business venture in downtown Dawson.

No, it wasn’t a new saloon.

It was an opera house.

That’s right. An opera house.

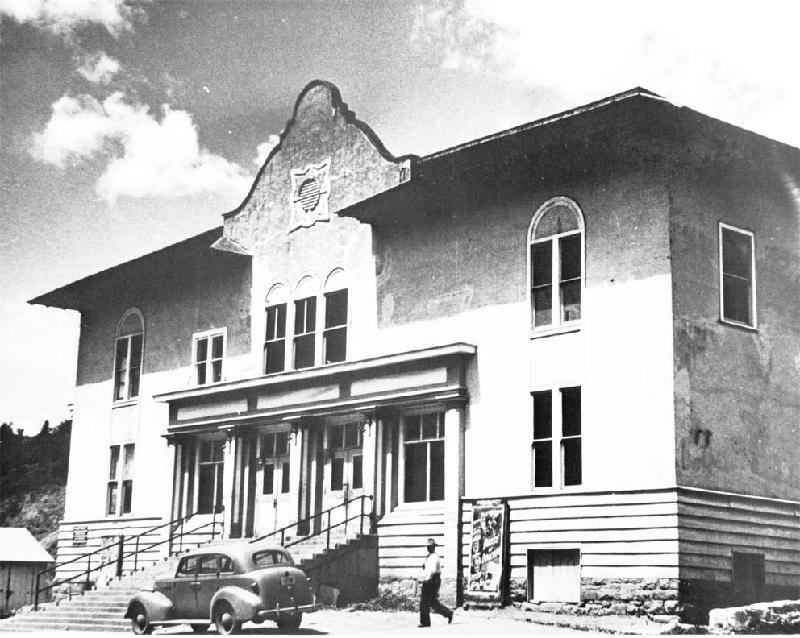

The new venue was the Dawson Opera House, a two-story, Mission Revival structure that kicked off its 43-year run that night with the Boston Ideal Opera Company’s performance of Edmond Audran’s comic opera “La Mascotte.”

Patrons paid as much as $1.50 for an orchestra seat in a theater “crowded from pit to its fullest capacity,” according to the Santa Fe New Mexican. At 1,000 seats, Dawson’s opera house became the largest in the territory, bigger than those in the larger cities of Albuquerque, Raton, and Santa Fe.

Nine months earlier, the Albuquerque Morning Journal reported that Phelps, Dodge & Co. had designated $25,000 to build an opera house as part of its plan to make Dawson “as nearly a model camp as there is in the southwest.” By this point, the company was well on its way to putting up 225 new four-room cottages to serve this growing mining community of 4,000 to 5,000 people.

Henry C. Trost of Trost & Trost, an architectural firm based in El Paso, Texas, was hired to draw up plans for the building. During this period, the company designed hundreds of commercial and educational structures in the Southwest, including the opera house and possibly the mercantile store for Phelps, Dodge’s mining operation in Bisbee, Arizona.

In May, the Raton Reporter wrote that the new theater building – now estimated to cost $40,000, or roughly $1.1 million in today’s dollars – would open on the Fourth of July. Not only would the 140-by-75-foot building serve as a venue for live opera, the newspaper said, but it also would house billiard rooms, bowling alleys, ice cream and soda parlors, and a 60-by-60-foot dancing hall.

The opera house did not open on July 4. But the Albuquerque Morning Journal reported on Aug. 5 that the building, capable of hosting “large spectacular productions,” was nearing completion.

“(T)he people of Dawson can feel proud of the fact of having one of the most modern theaters in New Mexico,” the story concluded.

Dawson wasn’t the first Southwest mining town with an opera house, but not many could compete in size or versatility. Besides the bowling alleys and billiard halls, the new building would play host to motion pictures, boxing matches, carnivals, circuses, political gatherings, school graduations, and more. It also doubled as a community center, supplying banquet and meeting rooms to fraternal groups and civic organizations.

Sadly, not all bookings were so festive. In 1923, the building was converted into a temporary morgue after 120 men were killed in a mine explosion. (An old company store served that purpose 10 years earlier when 263 men died in the country’s second-worst mine disaster.)

In 1909, Dawson’s opera house got a boost when J.J. Shubert of the prestigious New York theater family entered into an agreement to book productions through the Inter Mountain Theatrical Circuit, a Denver-based group with ties to more than 100 theaters in the West, including Dawson.

Shubert had business relationships with stars Fred Astaire, Eddie Cantor, Cary Grant, and Al Jolson, to name a few, though it’s not believed they ever graced the Dawson stage. Reports that Enrico Caruso, the famous Italian tenor, performed in Dawson between 1921-1926 also appears unlikely, given he died in Italy in August 1921.

Lydia Mendoza, a popular Mexican-American guitarist and singer, was among the performers who did play Dawson. Later in her career, she would perform for President Jimmy Carter at the John F. Kennedy Center in Washington and be inducted into both the Tejano and Conjunto music halls of fame.

The Dawson Opera House remained in operation until the closing of the town in 1950. Charlie Rosenfield, a Dawson electrician, purchased the building and used parts to construct a cabin in Ute Park, 30 miles southwest of Dawson. The cabin stayed in the family until it was sold earlier this year, according to niece Marlene Hancock Kotchou, whose father, William Hancock, ran the theater’s movie projector for years.

Unlike the historic opera house, the cabin is still standing.

Crosses of Iron

by Nick Pappas

Now available to order from:

University of New Mexico Press

… and other booksellers.

Audiobook version available to order from …

… and other audiobook sellers.